Note: I originally developed this as a programming exercise as part of a tutorial for the Qi programming language in the Racket language ecosystem. But as it is equal parts programming exercise and short story, I thought I’d post it here as well. You can read this post in one of two ways, either (A) as an “Advent of Code” style programming exercise that you can do in your favorite language, or (B) as a short story — just read and look at the pretty pictures. If you’re doing (A), I’ve signposted places where you need to write code by a paragraph consisting solely of “…”, so you know to pause there and write your implementation before continuing. In either case, enjoy the journey.

Thunder rolled through the walls like waves in a large pond that reach one end and come back again the other way, intersecting and repeating, never quite the same. The rumbling cascaded and repeated and attenuated until the next peal joined the subterranean chorus. Generations of philosophers had remarked on the unique quality of the sounds in this place, in these vast interconnected caverns in the interior of this particular mountain. The head monk opened his eyes and surveyed those assembled, some young and full of hope, others in retreat from a harsh world down there. All of them would find their place here. He paused and drew a breath, before beginning.

“Good morning, monks! I’m delighted

that you’re all here for you see

I’ve been slighted

by the fellow who came in here

and told me in words all too clear

that we’d never find the answers we’d sighted!”

The monks opened their eyes and cocked their heads all at once, at this revelation. The head monk went on,

“Too long have we endured this exile

Why there was a time they wouldn’t dream

of speaking to us so!

And now it’s all I can do not to scream

and insist that we get cracking (why, that reptile!)

’cause I say so!”

The monks, feeling decidedly chastened by this outburst, gathered afterwards in the hall outside. “Whoo whee!” Sridhara opined, nervously. “I haven’t seen him that mad since that time he went off on Hema about the rose petals.”

“Hmm? Did someone mention my name?” inquired a man leaning against the wall, rose in hand, smiling distantly.

“Oh, forget about him,” Halayudha said, “we should probably go somewhere where we can put our heads together and have something to show for it. Before Pingala throws us out! You guys coming?”

“Alright, lead the way!” said Sridhara.

Hemachandra peeled himself off the wall with a smirk and followed them out.

They gathered in one of the convenient and everpresent smaller caves that were used as dorms, at Bharata’s place, the usual hang out spot. That guy knows how to party. A chorus of “Hey, where were you?” greeted a confused Bharata as he opened the door.

“What?” he reacted. “Oh, yeah, I don’t really have a lot of time for that meditation stuff, Pingala is cool with it. Besides, I have a routine I’m preparing for the event next month and I gotta practice.”

“Alright well, practice later,” snapped Halayudha, walking in. “We’ve got work to do.”

“Man, you should have seen him,” chimed in Sridhara, in tow. “The guy was off the chain!”

“That’s enough, Sri. Look, apparently the townsfolk are growing impatient that we’ve promised them answers for so long and haven’t had anything to show for it since guruji’s glory days,” Halayudha explained. “As you can imagine, he’s.. a little upset, by the lack of faith, as anyone would be.”

“Uh huh.” Bharata listened. “You guys wanna dance?”

“What? No!” Halayudha replied, exasperated. “Look, let’s get some things figured out first, and we can dance later, okay?”

“Ah, sure. How can I help?” Bharata smiled.

The monks were confronted with the following problem:

Years ago, in his youth, guru Pingala, Rhyming Royal and head monk of the monastery, had observed that the meters that poetry could be composed in fell into several broad classes, and that you could find all possible forms of a verse of N syllables by enumerating the possible permutations of “short” and “long” syllables that add up to N. For instance, in the phrase, “I stared at the wall,” we linger on the words “stare” and “wall” longer than the others, even though they are each a single syllable just like “at” and “the.” Rhythmically, it was deemed essential to distinguish these in order to compose the best poetry. “And dance!” interjects Bharata, breaking the fourth wall. Oh right, also the best dances. “Are you going to tell them about rose petals?” Yes, yes, in due time. Pipe down, Hemachandra! “k, whatevs.”

The possible permutations of syllable types adding up to 3 syllables are:

SSS

SSL

SLS

SLL

LSS

LSL

LLS

LLL

… which we could think of as a binary enumeration of bits with 0s and 1s.

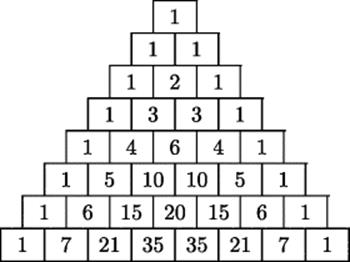

What Pingala had figured out in his youth is that if you had N syllables total to work with and you wanted to know how many subsets or “combinations” of K syllables you could make from these, that you could find the answer using a simple tabulation. First, you draw a single small square. Then, two squares below that, each halfway offset on either side of the one above so that they form a triangle. Then add three squares below that, extending the triangle in the same way, and so on. Fill the top square with the number 1, and each of the squares below that with the sum of the two numbers above it. By considering each square to correspond to a particular value of N and K, increasing downwards and to the right, respectively, the value contained in the square is the result you seek.

“Isn’t that the thing they call Pascal’s triangle?” you say (through the fourth wall)?

Precisely!

“Wait, who’s Pascal?” chimes in Bharata.

“Oh you don’t know Pascal?” Hemachandra replies, “He’s the guy that’s gonna ‘invent’ this in a few centuries.”

Right, er, regardless, Pingala gave it a different name, he called it “Meruprastara,” meaning, “the steps of Mount Meru.” He gave it this name by looking at the shape that he’d drawn on the ground, and looking up at the distant, curiously triangular mountain it seemed to resemble. It was on that day that he chose to make the pilgrimage to the mountain long associated with myth and legend, and to begin his long seclusion here, with the followers that he found along the way who sought the same answers he did.

“Let’s first retrace his steps, fellas!” Halayudha said. “If we’re going to make any progress, we need to understand the fundamentals.” “Oh, if we must,” rejoindered Sridhara. Hemchandra yawned pointedly.

Part 1.

Help the monks construct meruprastara. A mountain is only as stable as its foundation, and if we are to climb it, it would be expedient to take a, “bottom up approach,” if you will.

“Quit the corny humor, bro, just tell the story, alright?”

Okay! Jeez, Halayudha. Just be patient, man! Now, assuming there are no further RUDE interruptions, let’s begin.

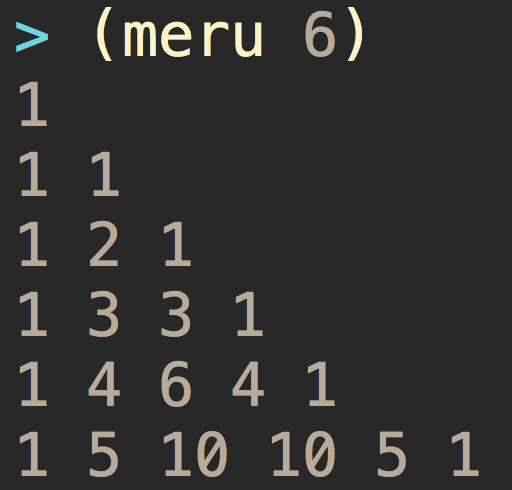

First, we’ll need a function that simply generates a single row of the triangle. Let’s write a function called meru-step that takes in a row as input, and generates the next one as output.

That is, write a function that has the following input/output profile:

1 → 1, 1 1, 1 → 1, 2, 1 1, 2, 1 → 1, 3, 3, 1

…

“Alright! Look at that,” approved Sridhara.

“Okay, cool. Now we need to be able to generate an arbitrary row of this given just the row number,” Halayudha added.

Write a function meru that accepts a number N as input and produces the Nth row of the triangle. E.g.:

2 → 1, 2, 1 6 → 1, 6, 15, 20, 15, 6, 1

…

Sridhara regarded the output and smiled. “Piece of cake! What now?”

“Um wait,” said Bharata, “Wasn’t there supposed to be a mountain somewhere in all this? I don’t see it. All we have is some numbers for the Nth row. How do we get the mountain to show up, again?”

“Right. Next,” Halayudha continued, “we need to actually ‘show the work’ that’s done on the way to calculating the Nth row. We need to see each row as it’s constructed, without affecting the computation of the row.”

“Spoiler alert: use a side effect, womp womp,” Hemachandra interjected sarcastically from the sidelines.

“That’s right,” Halayudha acknowledged. “As Hema says, in the loop that goes through each row on the way to computing the Nth row, we need to add a side effect to the computation of the row that prints it so we can see all of the rows computed along the way. That is, we don’t just want to output a result at the end — in fact, we don’t care about the result at all! We just want to see — in other words print — all of the computed rows on the way.”

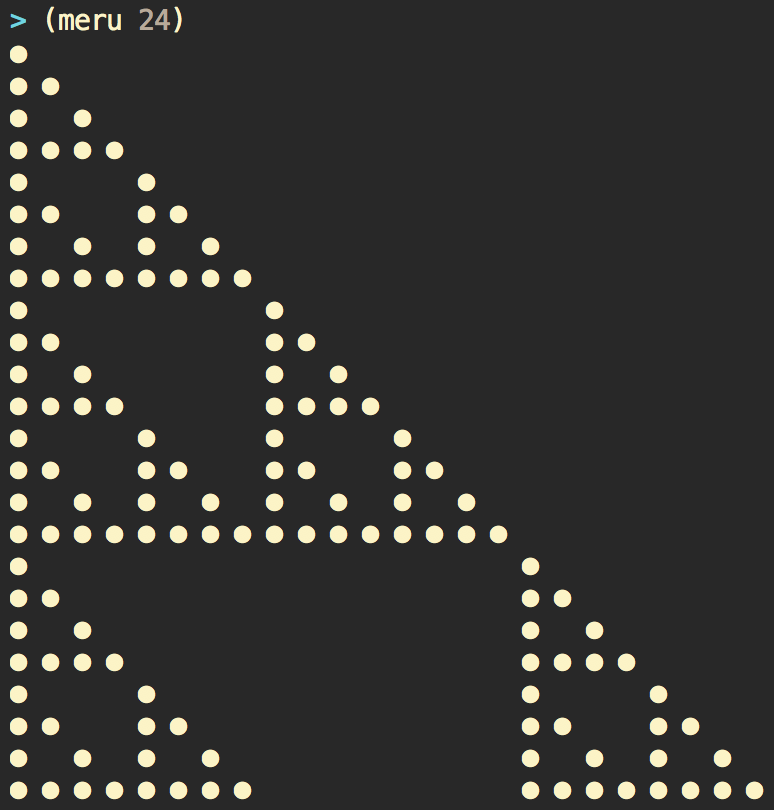

Modify your implementation of meru to include a side effect to echo each row to the screen on its own line, with the numbers within each line separated by spaces.

…

“Dang. Gives me chills every time,” Sridhara reflected.

“Boooring.” The others scowled at Hema. “What? We haven’t gotten to the good stuff yet!”

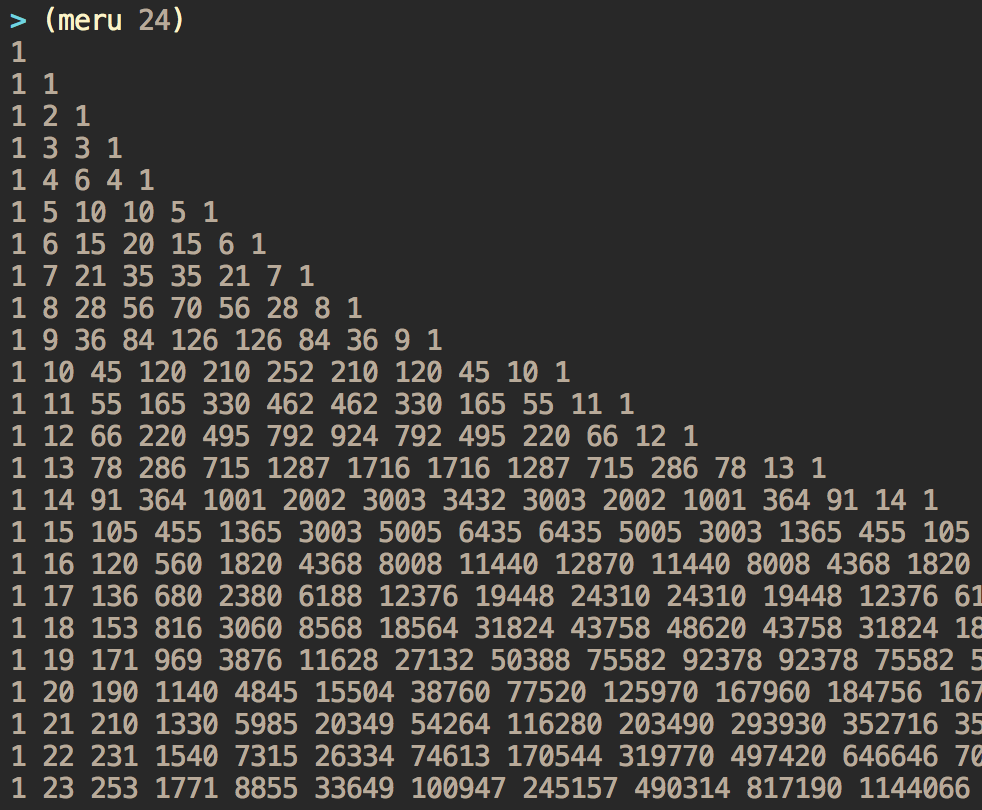

“The thing about this triangle here is that its shape gets warped as the numbers get larger. For instance, if we run it for 24 rows, it hardly resembles a triangle at all,” resumed Halayudha. “Try it and see.”

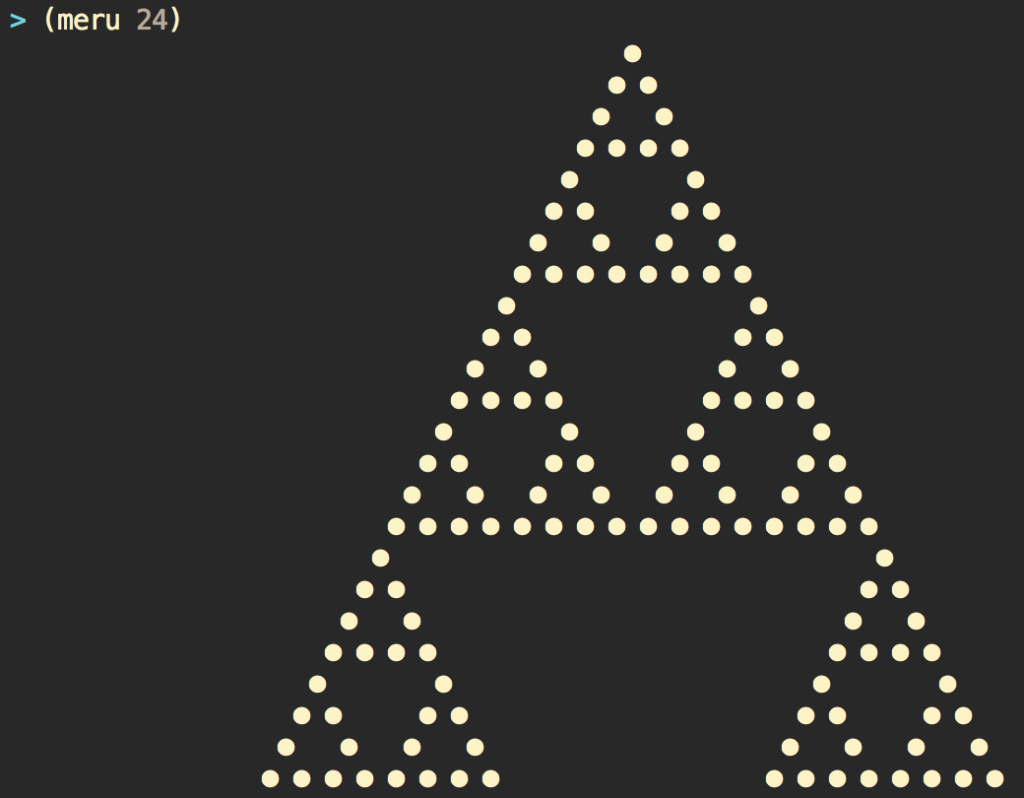

“So in the rendering function,” he continued, “let’s just print a * symbol instead, if the number happens to be odd, and a space if it’s even. That should help us see things a bit more clearly.”

Modify the side effect function to adopt Halayudha’s suggestion, and print 24 rows.

…

A distant sound was audible, and minuscule reverberations tickled their feet. “Quite a storm out there, huh?” Halayudha looked searchingly towards the door.

“Okay, great, now that we’re all caught up,” Hemachandra snapped, “there’s something that’s always bugged me about this. Look at those little boulders that make up the mountain — why are they shaped like that? The real boulders we’re surrounded by are circular, more like ●. Let’s use this symbol, if we want it to look like the real thing.”

“That’s just aesthetics, Hema, it doesn’t really matter to the essence of the problem.” Sridhara said, dismissively.

“Fine, let’s just do things the old way and get nowhere, then,” retorted Hemachandra.

“Alright look, it’s fine, it’s not a big deal,” interjected Halayudha hastily. “Hema wants boulders, let’s do boulders. No big deal, okay?”

Adopt Hemachandra’s suggestion to use the boulder ● instead of *.

…

As the mountain appeared before them, there was a great rumbling felt all around and the monks were flung to the walls.

“What in the..?”

“Ouch!”

“Oof!”

“My drum! I needed that for the dance!”

As they collected their senses, they noticed that the walls seemed to have rearranged themselves. Everything seemed a bit… odd, and there seemed to be a distinct one-directional slant to things.

“What… happened?”

“I don’t know. Is everyone OK?”

“I… think so. I can’t find my drum. I think it flew out the door!”

“Never mind your drum for now,” Halayudha said, nursing a sore shoulder and taking stock, “I think … I think I know what’s happened. I don’t understand, but… just look at that.” He pointed at the rendered triangle. It looked… just like the mountain that surrounded them. And just like the rendering, the real mountain now seemed to list heavily to one side as if drawn by some unseen force. “I think we’re on to something here, I just don’t know what. Hema, did you know this was going to happen?”

“What, me? No. I just like to indulge my keen sense of aesthetics — absent in most of my peers, unfortunately — and it often leads me to interesting things.” He held out his hand and regarded his fingers with an air of defensiveness veiled as superiority. “I didn’t think this would happen. In any event, don’t look at me, I don’t know what to do.”

“That’s just great.”

“Wait, I think I know.” interjected Sridhara. They turned to find him with a distant expression on his face pregnant with the verbal barrage about to ensue. “Not one of these again!” The monks braced themselves, and Sridhara burst forth:

“As our thoughts rise out of the morass of suffering and desire in which we’ve so long found ourselves, we too rise up out of what we were, and become… something else. We aren’t anything to begin with, don’t you see! We neither become nor do we not become, yet we transcend! It’s all so simple!”

“What the devil are you on about, Sridhara! Can you please get to the point?”

“Yeah, I’d really like to get on with it and find my drum.”

“I’m gonna use your head for a drum if I hear another word about it!”

“Oh yeah, well, why don’t you just try it, then?”

“Okay look,” Sridhara continued, “this is gonna sound crazy but, I think that our rendering of the mountain was so accurate that it really became the mountain, in some way. Our rendering of the mountain is the mountain now. We just need to re-render it to make it right. Otherwise we’ll be stuck this way, if you catch my, er, inclination.”

Oh, so I can’t make corny jokes, but he can?

“He’s actually in the story, you’re just the narrator!”

That’s right, and as narrator…!

“Shhh, listen! Do you hear that…?” Halayudha held up a hand for silence. They stopped, motionless, and listened. It was unmistakable. A low creaking and a gentle rolling. The rocks seemed to be under a great strain.

“The lopsided weight distribution is compromising structural integrity,” Bharata panicked. “Evasive maneuvers! Er, excuse me, I mean, we need to get this mountain sorted out, stat!”

Save the monks and bring balance back to the mountain. Assume that the mountain needs to be centered within the display, and that the display is 80 characters wide. “You can use this formula,” Sridhara adds, quickly scrawling out some notes on a piece of parchment, “each row needs to be offset from zero by a number of characters N = max(0, floor((display-width – length-of-row) / 2)). The floor is to ensure it’s integer-valued, and the max is to ensure it doesn’t go below zero. Here, take it, quick!”

Implement the logic to center the mountain in the middle of the screen.

…

Part III.

The very walls seemed to come alive and there was a great rhythm to the rumblings as things gently reoriented themselves. Bharata broke out in dance and the others joined him.

“Oh thank the Heavens!”

“We’re saved!”

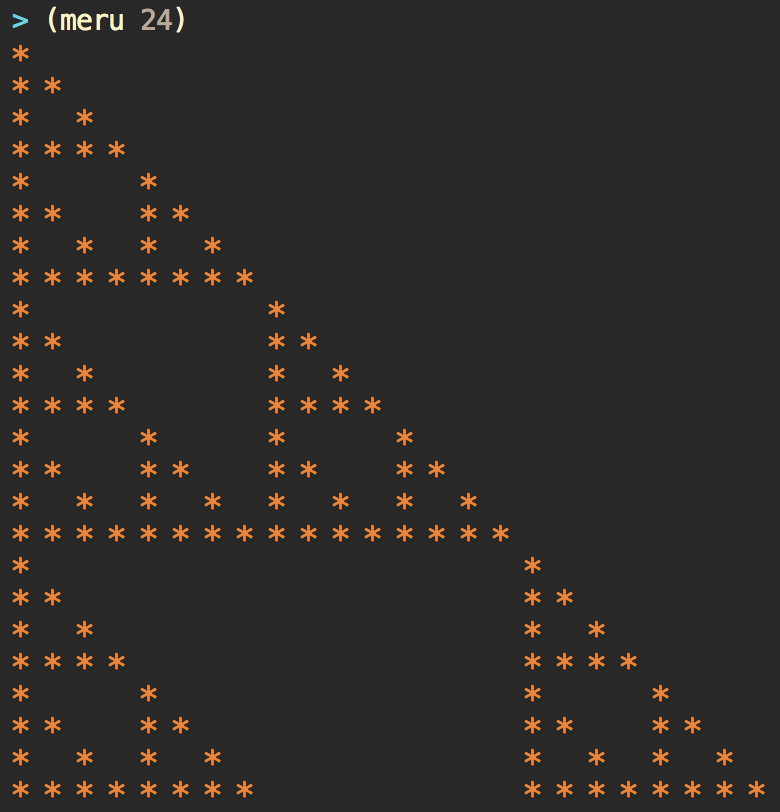

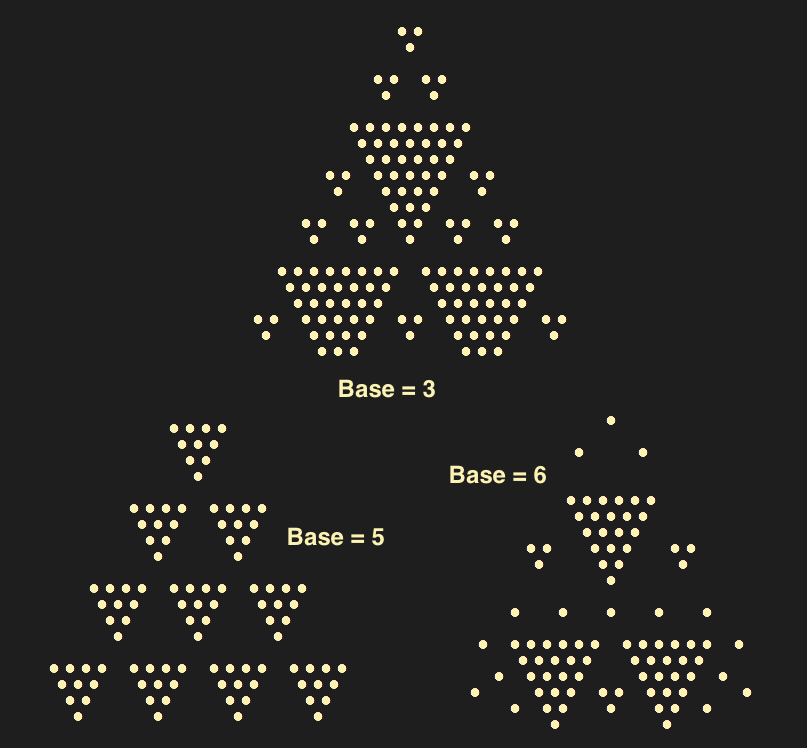

But while the others celebrated, Hemachandra looked like a man possessed, his distant nonchalance replaced by a knowing determination. “If selecting the odd numbers for display produces the mountain we know, then what if we employ different selection criteria?” he muttered to himself, furiously drawing shapes on the wall with a piece of chalk. Strange triangular patterns gradually appeared there as the others continued dancing. Finally, he comes to you.

“Look, the others are never going to agree to do what I’m saying, but we can’t stop now. True understanding requires boldness, requires daring! We can’t be content to understand only what we already know and have seen. We must dare to inquire about things that we do not see but merely suspect, which we must do even at risk of peril to ourselves. What good is a life lived if we never escape the confines of our own fears and limitations, isn’t that right? Look!” he points at the strange drawings on the wall. “Flip it around! Try displaying the even numbers instead, and print a blank for the odd ones!”

Let’s do what Hemachandra wants. It could be genius, or madness, but there’s only one way to find out. “Just,” Hemchandra grabs you by the arm and adds, “just keep the method of selection abstracted so we can parametrize the selection criteria, okay?”

Not sure what that means, but let’s just select the even numbers for printing instead of the odd ones, for now.

…

A great wind blows through the halls. Bharata’s drum flies by, followed by his Royal Rhyminess Pingala himself, seated in meditation and evidently unaware that anything unusual is afoot. “It’s just as well,” Hemachandra thinks to himself, “I don’t want to have to explain this to him just yet.”

Sridhara peeks out of a crevice, surveying the proceedings with a smile on his face, and winks knowingly at Hemachandra. Bharata looks absorbed in trying to walk in midair and can be heard to be vehemently denying a sordid love affair with someone named Billie Jean over the sounds of the wind.

“Boy, you’ve really done it this time, Hema!” Halayudha glowers as he floats past.

Hemachandra looks calm, under the circumstances, and coolly hangs on to a stalactite as he looks around. “That’s how you remember it, you know,” he says to no one in particular, “You gotta ‘hang on tight’ to a stalactite since it grows downwards from the ceiling. The stalagMITE on the other hand… Hey you!” He looks at you. “You seem smart. It’s fine, trust me. I got us into this and I can get us out. Did you do the thing I said earlier about keeping the selection criteria abstracted? I hope you did ’cause it’s gonna get us out of this.”

… Er, don’t look at me, I’m just the narrator.

“Look, don’t worry about it. Here’s what we need to do. Modify the selection criteria function render-step to accept a predicate and return a function. This returned function does what render-step formerly did, except that instead of using a hardcoded selection criterion, it uses the supplied predicate. If the predicate returns true on the input value, then the function prints a boulder, otherwise, it prints a blank. In other words, the rendering is now parametrized by a predicate that specifies the selection criteria, does that make sense? Now, once you have that working, I want you to write another function to return true if the input is a multiple of some pre-specified number. In other words, write a function multiple-of? that accepts two inputs, the first, a number N, and the second, the input value V. If V is a multiple of N, this function returns true. Got it?”

Okay, write a function multiple-of?…

“I already said that!”

Right, he did. Alright, it’s up to you! Here are some sample inputs and outputs, go!

2, 4 → true 2, 5 → false 3, 9 → true 3, 10 → false

Oh, and don’t forget to parametrize render-step!

…

“Nice! Now here’s where it gets tricky. We need to pre-specify a base in the multiple-of? function, for instance, 3, before passing it to the selection function as a predicate. That is, we need to define a closure on the multiple-of? function with the argument 3 passed in, which gives us a new function that retains awareness of the argument 3. Now, passing this to the selection function will mean that it will print a boulder for numbers that are multiples of three, and blanks if not. Try this with different bases and see how things look!”

…

Part IV.

Things are mysteriously calm in the interior of the mountain. Boulders and walls shift and change before their very eyes, but it seems almost normal, somehow, like they’re on the verge of finding something out that’ll make sense of all of this. Entire gaping caverns come and go around them, and they look at each other with increasing calm.

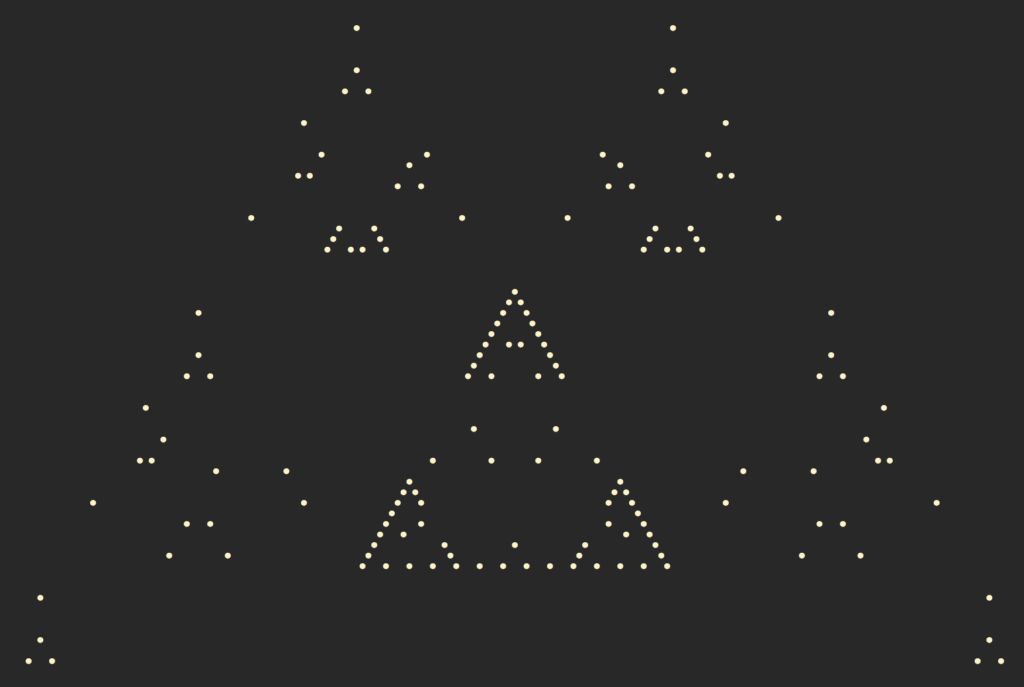

“I have it,” Sridhara says at last, and everyone looks at him. “It’s too complicated to explain. I’ll just let you see it. Let me think, ah yes, multiples of 9, with remainder 2, and about 90 rows. Does that sound right?” The others consider for a moment, and then one by one they nod in agreement.

Alright, let’s look at what Sridhara realized. Modify the multiple-of? function to take in an additional argument R, so that the arguments are N, R, V, where N is the base and V is the input value, while R is the remainder to check for (instead of 0). This function answers in the affirmative for inputs V that leave a remainder of R when divided by N.

…

Okay, we’ve got it now. Following Sridhara’s suggestion, pre-supply (via a closure) the arguments 9 for N, and 2 for R. Center the triangle by setting the display width to 200, and print 90 rows.

…

…

…

…

…

“Meru’s no mountain,” Halayudha observes. “It’s a metaphor for the quest for answers. The base of the mountain represents a strong foundation. The interminable steps to the summit represent a difficult journey, and progress, one step at a time. Our long seclusion within represents patience and introspection. And all to realize that the greatest of all mountains to be seen in any direction is the span of our own being.” Just then, Pingala levitated into the room.

“So it’s you lot that’s to blame!

Hema, Sridhara, even you Halayudha?

Progress and answers are all very well

But permuting the place like it’s just some

characters on a screen, what the hell,

you could be considerate, you know, all the same,

and give a thought to the side effects, by Buddha!

By the way, I think I found your drum.”

So saying, he handed the drum to an overjoyed Bharata. “Oh, and, uh,” he paused, adding, “nice work.” He smiled in way that suggested either skeptical approbation or a trap soon to be sprung, and the well-weathered monks didn’t dare say anything lest they be caught in it. “Now,” he thundered, “clean this place up!!!” With that, he turned and floated away.

Well, that’s it for now. Sounds like the monks have their hands full, as you can imagine. That’s all folks!

“… Typical. Just typical.” Er, what? “I knew you’d forget about the rose petals. Just pointing it out. I didn’t really think you’d remember, anyway.” Oh, whoops, I’m sorry Hemachandra. “Nah it’s all good. That’s why I only rely on numero uno, know what I mean?” Look, I didn’t know where the narrative arc of this thing was going when I started. It just ended up being about the triangle and not the sequence, okay? We’ll do the sequence another time, maybe. Hemchandra just smiles and walks off, waving dismissively, pretending not to care. Rose in hand. “I really don’t, you know,” he says, as he recedes out of earshot.

Author’s note: The characters in this story are real prosodists and mathematicians involved in the long history of the study of combinatorics, of which the triangle commonly known as Pascal’s triangle is a recognizable symbol widely employed in computer science education. The story is, of course, only loosely based on their actual lives and personalities (about which I know very little. I selected the characters on a whim after skimming this paper), and the actual individuals described are not really contemporaries, but rather were separated in history by centuries, even millennia. I bet they’d’ve gotten along, though. “Eh, we don’t really like each other that much, to be honest.” Guys, author’s note? “Yeah, I just tolerate these guys ’cause they’re at my BEhest.” “Nobody listens to you! Don’t be immodest.” “I’m just around for the parties.” The others look at him. “… that I’ve been promised!” “Boots n cats n boots n cats n …”

Christmas Challenge: Since today happens to be Christmas Day, here’s another challenge for you, dear reader: is it possible to make the mountain resemble a Christmas tree? Follow up: for any symmetrical shape, is there always a set of (simple-ish) selection criteria that will generate a rough approximation of that shape somewhere within the mountain? (I don’t know the answer to these. Share your findings in the comments ☺️ )

Another author’s note: If you happen to know something about Sanskrit prosody and if I’ve gotten something wrong in my characterization of the considerations regarding syllables, please correct me in the comments! Bharata takes a break from their shenanigans to add, “Yeah, I’m not sure it’s really about ‘short’ and ‘long’ so much as ‘light’ and ‘heavy’ — so it may be more about emphasis than duration, but I’m too busy to explain it to you right now… Yo guys! Check me out, I just made this one up while we were floating around… Billie Jean, whoo! …” Uh ok, thanks Bharata.